Uncovering Joseph Bologne, the ‘Queer Chevalier’

A Queer Georgian Social Season is a grassroots programme of events designed to challenge perceptions of queer identities in the 18th century, with a focus on classical music. Ahead of a planned partnership with The Mixed Museum, Associate Creative Director Warren Reilly reports on a recent event celebrating the life of the mixed composer Joseph Bologne, Le Chevalier Saint-Georges – and reflects on the musician’s impact on Warren’s own artistic journey.

The museum’s Director Chamion Caballero and I were honoured to be among guests at a recent celebration in London of the life of Joseph Bologne, Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

Held in the Music Room at Burgh House in Hampstead, Bologne: Queer Chevalier was the latest in a series of events held by A Queer Georgian Social Season, this time to mark Black History Month 2023.

The salon-style concert explored the early life, sexuality and musical career of the French violinist, conductor and composer through an ‘interview’ with Bologne – as played by drag king Shardeazy Afrodesiak – and performances by the ensemble Les Bougies Baroques.

As a queer, mixed race Londoner, this event was nothing short of transformative for me. It was empowering and emotional to have the genius of Joseph Bologne brought to life in such remarkable surroundings.

Like other events in the series, this felt like a place where my own intersectional identity was not only acknowledged but celebrated.

A Queer Georgian Social Season

Burgh House in Hampstead is home to A Queer Georgian Social Season, a grassroots queer programme of events that runs from Pride Month in June to UK Pride History Month in February. Now in its second season, the programme aims to highlight stories of queer history during the 18th century, spanning from the beginnings of the Georgian period through to the Regency Era, with a focus on classical music. Through this, it challenges the idea of queer austerity in history, showing that queer people have always been central to society and culture and in fact were far more visible and accepted than we might think. The season was founded by the director of Burgh House, Mark Francis-Vasey and Ian Peter Bugeja, the Founder and Executive Director of the vocal and period instrument ensemble Les Bougies Baroques, who is himself of mixed heritage.

Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges’s early life

For those not familiar with him, it’s simply not possible to summarise the Chevalier’s extraordinary life in a few paragraphs, so you’ll have to forgive me for going into some detail here.

Joseph Bologne was born on Christmas Day in 1745, the son of a wealthy planter, George de Bologne Saint-Georges, and Anne, also known as Nanon – an enslaved African woman who worked in the family home.

Though many plantation owners sold their mixed race children born to enslaved women, this was not the case with George. When he was accused of murder and had to flee Guadeloupe for France in 1747, he did everything in his power to ensure that Nanon and their child would evade the clutches of those who sought to sell them after the local authorities claimed his estate.

On 1 September 1748, young Joseph, accompanied by George's wife, Elisabeth Mérican, his half-sister and his mother Nanon, set sail for France. By early January 1749, they had made their home in the Saint-Germain district of Paris. After two years, a royal pardon allowed them to return to Guadeloupe.

Back in Guadeloupe, however, the French government's decrees threatened the freedom of those born of mixed racial heritage. George realised the strict limitations France’s Code Noir (French for ‘Black Code’) imposed on his son and Nanon, prompting a pivotal decision to send Joseph to France in 1753, where he attended a prestigious boarding school. Two years later, his father and Nanon – without Elisabeth – returned to France where they moved themselves and Joseph into an apartment in the prestigious Rive Gauche area of Paris.

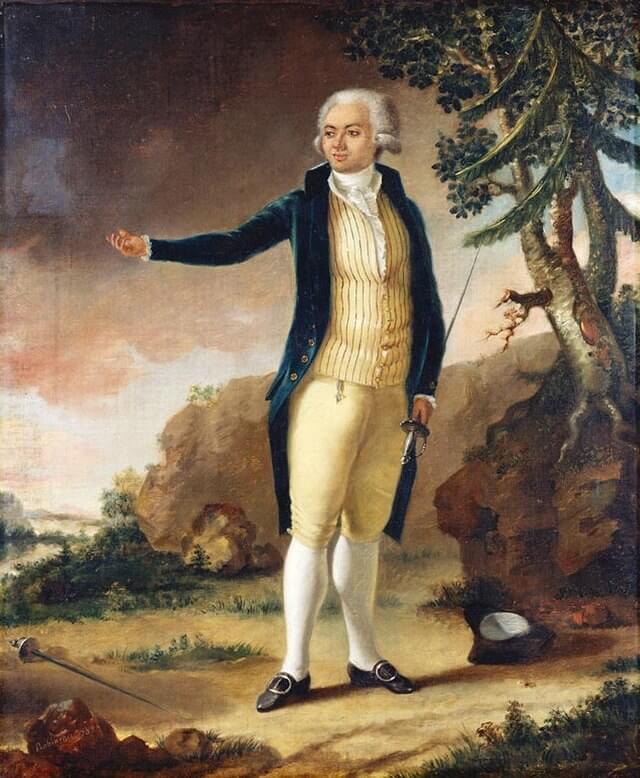

In France, Joseph experienced the privileges of an aristocratic education but was not immune to persistent racism. At the age of 13, he entered the Royal Polytechnic Academy of Weapons and Riding, honing his skills under the guidance of Nicolas Texier de la Boëssière, a notable figure in the evolution of modern fencing. By 21, he was considered the best swordsman in France.

In 1761, Bologne was appointed an officer of the king’s bodyguard in Versailles and given the title ‘Chevalier’. From then on, he adopted the title Chevalier de Saint-Georges, after his father’s plantation in Guadeloupe.

But his talents did not lie only in fencing – he was apparently gifted at everything he did. After a visit to Paris in 1779, John Adams, who went on to become the second President of the United States, called him “the most talented man in Europe in horse-riding, shooting, fencing, dancing and music.”

Royal society, activism and an assault: Joseph Bologne in Britain

Relevant to the mixed British history that we showcase at The Mixed Museum is the fact that the Chevalier made two extended trips to the UK. In 1787, he fenced before the Prince of Wales – who later became George IV – including against the Chevalier d’Éon, who lived publicly as a man and a woman during their lifetime. The event is captured in a painting by Robineau.

During Saint-Georges’s second visit in 1789 – a month after the fall of Bastille during the French Revolution – he lived lavishly and enjoyed the company of the Prince of Wales, who took him hunting, fencing and to the races. The Chevalier also became involved with the anti-slavery movement, meeting regularly with William Wilberforce and other prominent abolitionists, and translating British anti-slavery tracts into French. It is suspected that his activism was the reason he was attacked on the streets of Greenwich by five armed men – incredibly, Saint-Georges managed to fight them off.

The Chevalier Saint-Georges’s musical journey

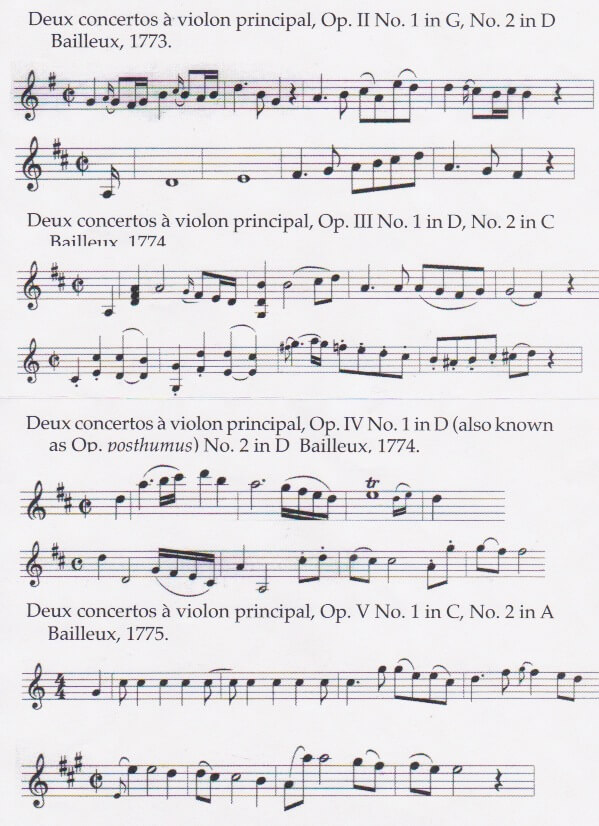

Little is known of Saint-Georges’s early musical education, but he wrote his first composition, Op. I – a set of six string quartets probably inspired by Haydn’s early quartets – in 1770 or 1771.

He made his public debut as a violinist with Francois-Joseph Gossec’s Concert des Amateurs in 1772, later becoming the orchestra’s musical director and turning it into one of the best in Europe. He debuted his first violin concertos, Op. II, with the ensemble.

Although he was favoured by Marie Antoinette, the last Queen of France, becoming a frequent performer at her exclusive concerts at Versailles, he was not immune to the prevailing attitudes of the time. In 1775, his bid to become Director of the Paris Opera was opposed by artists who objected to his mixed race background. They petitioned the Queen to block his appointment, and he withdrew his candidacy to avoid her embarrassment.

His military career – he became the first Black colonel in the French army and formed a regiment of 1,000 Black and mixed race soldiers – and later life in poverty only add to his extraordinary story. He died in Paris in 1799. His fall into obscurity following his death has been blamed, in part, on racism.

Introducing Madame du Reilly

Learning more about Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, inspired me to create a new drag persona: Madame du Reilly. This persona draws inspiration from the narratives of William Hogarth's A Harlot's Progress paintings, the scandalous life of Madame du Barry, the maîtresse-en-titre to King Louis XV of France, and Joseph Bologne’s story of migration and excellence.

In my imagination, Madame du Reilly's story unfolds against a backdrop of opulence and intrigue, mirroring the tumultuous lives of these historical figures. She allows me to explore the rich tapestry of queer history while expressing my own queer identity.

Like A Queer Georgian Social Season, with whom the museum hopes to explore more queer mixed histories, the aim of this new character is to challenge the prevailing norms of society, forcing us to confront uncomfortable truths about race and privilege and the power of creativity to transcend boundaries.

Exploring Saint-Georges’s queer identity

For me, the particular beauty of the evening in Hampstead was to hear elements of Saint-Georges’s story interpreted by queer historians and performers.

Ian Peter Bugeja, Director of A Queer Georgian Social Season, is passionate about highlighting queer history within classical music, and the scene was set by my drag alter-ego, Madame du Reilly, introducing the evening alongside Amber Kation, a Georgian drag character created by Bugeja’s husband, Dominic Myles Bugeja-Lane.

Saint-Georges and Lamotte

We then enjoyed the drag king Shardeazy embody Saint-Georges, in conversation with Bugeja, providing a contemporary perspective on the events that shaped his extraordinary life.

Bugeja highlighted that it was widely reported during Saint-Georges’s life that he and his male friend Lamotte were described as “inseparable”. Saint-Georges’s friend Louise Fusil, a singer at the time, compared them to Orestes and Pylades.

The Director of A Queer Georgian Social Season explained that this was widely understood in the 18th century as alluding to an intense, romantic, possibly homoerotic relationship between two men. He went on to suggest that this coded reference, coupled with the fact that Saint-Georges never married, suggests that his sexual orientation might be one we would now describe as bisexual or pansexual – if we need to classify it at all.

Bugeja relayed that – according to the violinist Gabriel Banat, in his book The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow – Lamotte (also known as Lamothe) had known Saint-Georges from their childhood in Guadeloupe, where he appears to have been one of the few white friends he had of his age. Lamotte was probably the son of Vidal Lamothe, the manager of Saint-Georges’s father’s plantation. He would go on to become a horn virtuoso, playing in the King’s orchestra, and Saint-Georges’s longstanding friend.

The 'Black Mozart'... or the 'white Chevalier'?

Bugeja also sought to counteract a common characterisation of Saint-Georges, saying: “It’s worth reconsidering the ‘Black Mozart’ label and perhaps calling Mozart the ‘white Chevalier’ instead.” An interesting point, since there is evidence that Saint-Georges influenced Mozart.

Then came the concert, featuring musicians from Les Bougies Baroques, conducted from the harpsichord by Bugeja and led by violinist Christopher McClain, who has performed with ensembles including the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

Being surrounded by fellow artists and creatives who shared my passion for both queer and Black histories was profoundly moving, offering a sense of belonging that is often missing in more conventional spaces.

With many thanks to Ian Bugeja for research assistance on Joseph Bologne's life.

Burgh House photos copyright of Warren Reilly and Dominic Myles.

Learn more

Read more about the Chevalier de Saint-Georges on Wikipedia

Find out about the next event in A Queer Georgian Social Season

Watch Les Bougies Baroques in action