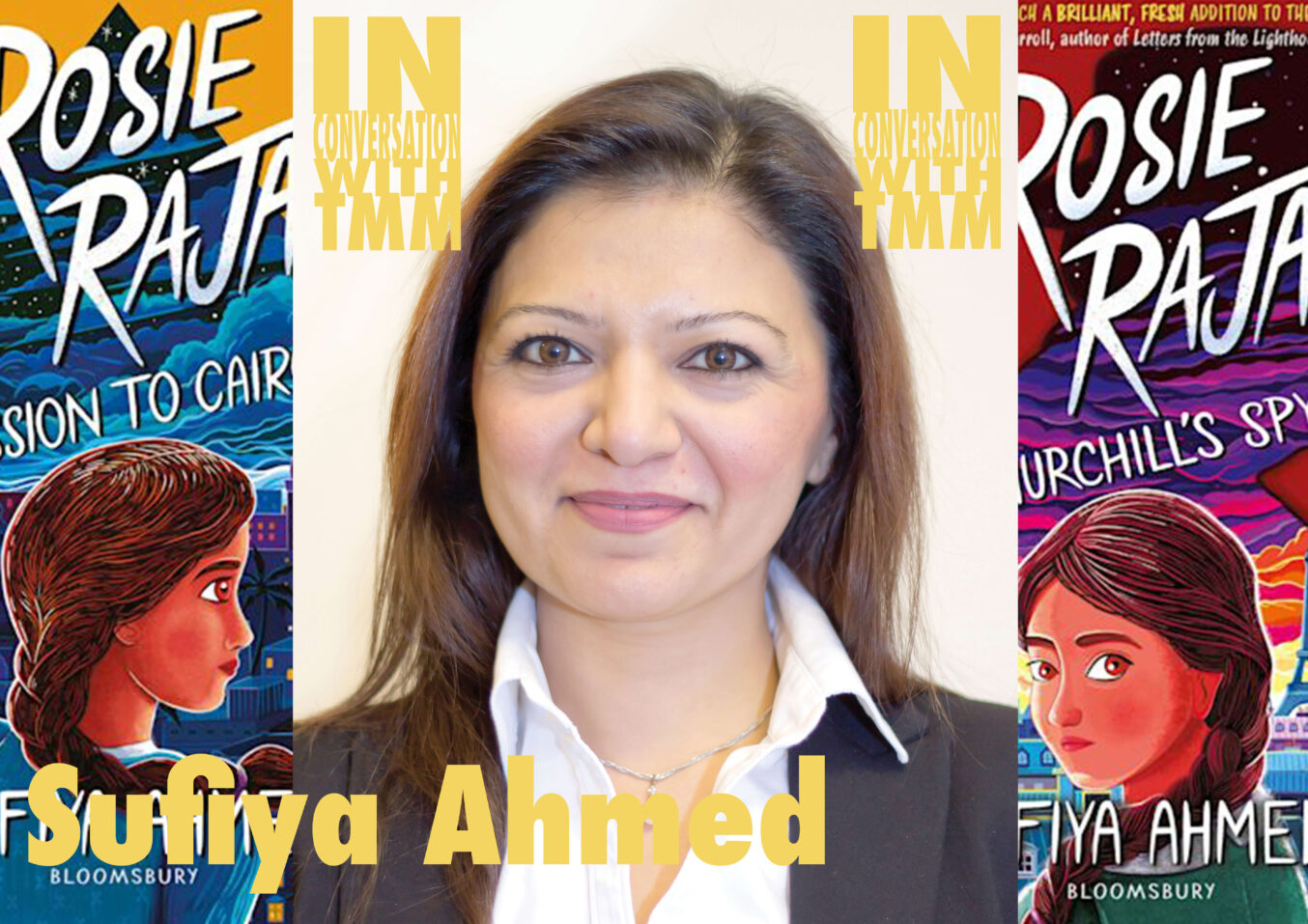

Sufiya Ahmed is a children’s author and girls’ and women’s rights campaigner whose Rosie Raja series follows the adventures of a mixed Indian and British girl who joins her father as a spy during World War Two. We talk to her about her determination to bring Britain’s shared history to life – and why Black and brown writers don’t need permission to tell our stories.

Many of your books centre British Asian characters and experiences. Why is that important to you?

Most of my writing is a reflection of my political activism. I spent a long time working in Parliament, and for years I’ve run something called a Girls Rights Workshop, where I go into schools and teach young people the practical skills they need to campaign for girls’ rights: how to write to your MP, how to write a press release. Before we start, I always do a little presentation about role models, and I include two Asian women in it: Noor Inayat Khan, the British resistance agent who served in the Special Operations Executive, and Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, the suffragette. And I noticed that, never mind the children, not even the teachers knew who these two women were. So I thought, ‘I’m going to change that’. These were real life figures who contributed to this country. So for me, it was wanting to write stories about this history – some people call it ‘hidden history’, but I prefer to call shared history. How we think of ourselves depends on the stories that are written, and I wanted to bring these ones into our country’s narrative.

How we think of ourselves depends on the stories that are written, and I wanted to bring these ones into our country's narrative.

Why do you think it’s important for people, particularly the children you write for, to get a sense of that shared history?

People might say, ‘It’s just a story’. But with historical fiction, you are bringing to life characters from history who might not otherwise be mentioned in schools. When I was growing up, I loved history because I love stories. But sometimes I felt that I was peeking into someone else's history, because the people we were taught about did not look like me. But actually, there were lots of people who look like me who contributed in a big way. During World War Two, five million soldiers came from the Empire to fight, 2.5 million from India alone, but they’re just not mentioned in our history books. If I had known that it would have helped my sense of belonging. And it’s not just for children of colour: it’s for all children to understand why this country looks the way it does. That because of 400 years of empire, Black and brown people are part of British history. For example, Princess Sophia Duleep Singh, was a leading figure in the suffragette movement. She was very, very close to Emmeline Pankhurst. And if you look at photographs of the suffragettes giving speeches, she’s right there, in her couture, the best dressed woman there, but just ignored, just washed over. So it’s about who records the history. They didn’t write about these stories, but we can.

Do you think there’s now a greater willingness in publishing to explore these stories?

Yes, I think the industry has seen a major shift. But that’s because of the wider conversations that we’ve been having in society, which has led to a real push from schools to have a more inclusive curriculum. If those schools are willing to buy these books, then publishers will publish them.

Sometimes people describe the kind of books I write as ‘alternative history’ or ‘diverse history’. I find that quite strange and ‘othering’. This isn’t a Marvel world where there are different universes going on: it’s one history.

Why does representation matter?

Children need to see themselves and others who look different from them in stories. Stories are mirrors and windows. If there are no children of colour in stories, you’re not reflecting society. But I’m not that keen on the ‘representation matters’ hashtag. I may have used it in the past but I don’t now. The writer Toni Morrison has talked about the purpose of racism being to distract us from our work. I think we need to move beyond that point where we are constantly saying, ‘I count, let me stand here’. No. I don’t think we need to be asking anybody for permission. Sometimes people describe the kind of books I write, or other, Black, authors write, as ‘alternative history’ or ‘diverse history’. And I find that quite strange and really ‘othering’. This isn’t a Marvel world where there are different universes going on: it’s one history. The most important thing is that we’ve turned a corner in children’s publishing for inclusive stories in the last six or seven years and we need to build on that.

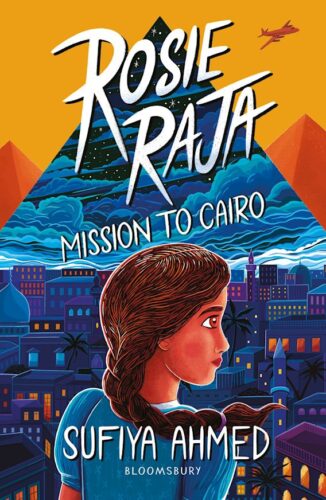

Your Rosie Raja series is based on the adventures of a mixed British and Indian girl growing up in the early 20th century, who finds out that her father is a spy. You’ve said that Rosie’s character was inspired by the British resistance agent Noor Inayat Khan. How did you first learn about her?

At home, my father has always encouraged Islamic history, and Indian history, so I always knew about Noor. She was a Muslim, and she was the great, great, great granddaughter of a very famous Sultan in India, Tipu Sultan, who was one of the last rulers to fight against the British East India Company, before he was betrayed by his prime minister.

We appreciated the nuanced way you developed Rosie’s character: not positioning her as confused or marginal, yet also recognising the issues she faces as a mixed race child. Why did you decide to make Rosie mixed, and how did you learn about these experiences?

It was really important to me to bring the Indian element in. Even though it’s a World War Two adventure set in Europe, we had this whole link, with Indian soldiers coming over, and the freedom movement happening in India at the time. So the main character, Rosina, had to be Indian. But it’s a spy story, so she also had to blend in in Europe. So that was one of the reasons why I made her mixed race: her colouring is very much her father’s and she passes as a French spy because of her dark hair. On a deeper level, as British people with heritage from other places, you can say that we have a foot in both worlds as well. I’m Indian, and growing up, at home, we’d have Indian food, customs and traditions. But at the same time, we have a foot in wider society. So when I thought of Rosie, I just thought of how I am.

Over the series, you grapple with the complexities of Rosie and her father being on the British side at a time when Britain still ruled India, which was in the middle of an independence movement (India gained independence in 1947).

From what I’ve read, there was this belief from those involved in the war that it needed to be won, because Hitler was so evil. People like Noor are on record as saying, ‘We’ll deal with independence when the war is over’. Which is exactly what happened. There were other people at the same time, Gandhi for example, who just wanted Britain out of India at the time. And others who felt that the war was nothing to do with India. So it was never straightforward.

Where do you think your determination to change things come from?

I’ve always believed that if you want change, you have to do it yourself. I always wanted to be an author, and if I’m fortunate enough to be published, then I’m going to write the story that I want to write. Stories can make such a difference to a child’s understanding of the world. When I do school visits, I always get asked, ‘What books have made a difference to you?’. And I always quote Of Mice and Men. It was the first book that helped me understand what racism was, what sexism was. There was racism in my childhood and I wasn’t able to process it – you were called the P-word and you just ignored it. But that book really helped me understand. If people read the Rosie Raja books and get a better understanding of the Indian contribution, or of the empire, great.

You’ve spoken about the importance of libraries in expanding your world view. What did you love reading when you were young?

I grew up on a council estate and we didn’t have much money to buy books. I think my mum only bought me one book, and it was The Twits by Roald Dahl. But I was reading whatever was available in the library, and the library had shelves and shelves of Enid Blyton books. So I was reading those and Roald Dahl and all the classics.

You worked in advertising and politics before becoming a full-time writer. How did you make the transition and do you bring elements of those previous careers into your writing?

I was about eight years old when I decided I wanted to be a writer. I had quite a strict mum and dad, and the public library on the council estate where I grew up was the only place where I was allowed to be alone. So I’d spend all my time there and get lost in these different worlds.

But publishing is quite hard. I did try to get published when I left university, but it didn’t really go anywhere, and there was also the pressure from my parents and myself to earn money and build a career. So I ended up in advertising. But I was always a political activist from the time I was at uni. And I decided after a while of working in the city that I didn’t want to make my directors any richer – I wanted more. So because of my interest in girls’ and women’s rights, I made the move into parliament, and worked as a parliamentary researcher. I was still writing books, still getting rejections from agents. It was after 10 years in that role that I finally got my first deal with Penguin, in around 2012, after being shortlisted in a writing competition. So I always wanted to be a writer, but it didn’t actually happen for two decades. That writing competition opened the door to making my childhood dream come true.

Sufiya Ahmed has lived in London since she was five years old. She worked in advertising and the House of Commons before becoming a full-time author. In 2010, she set up the BIBI Foundation, which arranges visits to the Houses of Parliament for children from underprivileged backgrounds. Her books include Secrets of the Henna Girl (2012), My Story: Noor-Un-Nissa Inayat Khan (2020) and My Story: Princess Sophia Duleep Singh (2022). The first book in her new series, The Time Travellers, will be published in February 2024. She can be found @sufiyaahmed on X (formerly Twitter).

See a full list of books written by Sufiya Ahmed

Read about our research into the Indian sisters and princesses Prativa and Sudhira Devi who lived in Britain in the first half of the twentieth century